Besim Dragovic (Boise State University) Paul G. Starr (Boston College)

Subduction zone field geologists are a proud bunch. In 2011, the name ExTerra (Exhumed Terranes) was coined to describe those in the GeoPRISMS community who investigate rocks exhumed from fossil subduction zones, rocks whose evolution illuminates processes otherwise hidden beneath the surface of active subduction systems (kudos to Sarah Penniston-Dorland and Maureen Feineman for the name “ExTerra”).

Traditional field studies have often been conducted by individuals or only small groups of researchers. One fundamental aspect of this project, termed the ExTerra Field Institute and Research Endeavour (or E-FIRE for short) was to conduct collaborative fieldwork to collect materials held communally, foster broad interactions through workshops, and incorporate student exchanges among research laboratories. The E-FIRE group consisted of researchers (including seven PhD students and three postdocs) from nine U.S.-based universities and research institutions, each with different analytical expertise in metamorphic petrology and geochemistry (e.g. stable isotopes, geochronology, thermodynamic modeling).

In addition, ExTerra partnered with a sister European organization, the ZIP project (Zooming In between Plates). The ZIP project, coordinated by Philippe Agard, consists of researchers from twelve universities across Europe with support from a number of different industry partners. The project has been running since 2013, with many of the twelve PhD students being in the final stage of their projects when we arrived in the field this summer.

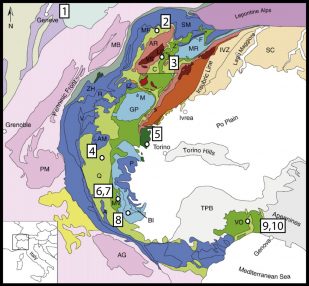

The overall big picture of this project was to trace the cycle of rocks and fluids through the subduction process. For this, we proposed to go to the Earth’s premier example of a fossil subduction zone – the Western Alps, Europe in the summer of 2017.

Planning and logistics

Weekly Google Hangouts offered the early stage researchers an opportunity to discuss papers on Western Alps geology and conduct webinars on analytical techniques, modeling, and field observation. In addition, an important component of the E-FIRE initiative was to have open, collaborative documentation and data sharing, with the end goal of opening the complete sample and data collection to any future researchers interested in subduction zone research. Hangout sessions before fieldwork included discussion with Frank Spear about the use of MetPetDB (a global database of various metamorphic petrology data) and with members of SESAR (System for Earth System Registration) about utilizing International Geo Sample Numbers (IGSNs – unique numbers and barcodes given to each sample).

One of the first major steps in the E-FIRE project was the first joint E-FIRE-ZIP workshop/retreat held in the Marin Headlands, close to San Francisco, in December 2016. This was the first time many of us had met in person. It provided a great opportunity for everyone to get to know each other. We also got to see some of our first subduction zone rocks together during a mini fieldtrip to nearby outcrops of eclogites and blueschists of the Franciscan Complex. It was also exciting to have such a large group of young researchers, from across North America and Europe!

Much of the credit for the fieldwork planning and organization must go to the E-FIRE PI triumvirate of Matt Kohn, Maureen Feineman, and Sarah Penniston-Dorland, as well as our main European collaborators Philippe Agard, Marco Scambelluri, Othmar Müntener, Samuel Angiboust, and their students.

E-FIRE Group Fieldwork overview – 7/26/17 – 8/6/17

This would turn out to be a different field experience for many of us. At any one time, there were 25-30 of us in the group, including our European collaborators. For a majority of the time, we stayed in Italian hostels and rifugios with beautiful mountain vistas (I know what you’re thinking…rough stuff). Thankfully, it just so happens that many of the world’s premier metamorphic rocks are associated with many of the Alp’s premier mountains: the Matterhorn, the Dent Blanche, and Monviso. Lunchtime in the field would often consist of grab bags of breads, cheeses, and cured meats from the local market (don’t worry, we ate some fruits and vegetables).

After a few close scares with delayed flights, everyone arrived safely in time for our first group E-FIRE dinner in Geneva. The next morning, we headed off for our first day in the field, consisting of an introduction to Alpine geology with rapid-fire stops along the way driving from Geneva to the Aosta Valley in Italy. This part of the trip was led by Alpine geology maestro, Philippe Agard, who demonstrated an incredible ability to explain complex Alpine features whilst hand-drawing cross-sections in front of some fantastic Alpine vistas.

No trip to the Alps would be complete without a hard slog up some steep mountainous terrain and our second day in the field delivered just that! Having hiked up some 1200 m of relief (most of us still suffering from jetlag), we were rewarded with spectacular views and some equally exciting geology in the Dent Blanche area. This area is interpreted to be a well-exposed example of an ancient subduction interface, where continental material of the colliding overlying plate is juxtaposed against the lower plate of European affinity. Recent work by some of our European collaborators, led by Samuel Angiboust, has suggested that this could be one of the best natural analogues for a subduction zone interface near the base of the upper plate crust.

Our third day started with an immaculate view of Monte Cervino (or it’s more well-known German name, Matterhorn). A beautiful mountain-side trail took us up to Lago Di Cignana, an artificial lake located in Valtournenche, in the Aosta Valley. This site is most well known as an ultra-high pressure (UHP) locality, consisting of various coesite (high-pressure polymorph of quartz)-bearing eclogites and schists. Recent work has found evidence for micro-diamonds within fluid inclusions in garnet, suggesting that these rocks were buried to depths greater tha 100 km and potentially provide a unique record of processes occurring deep within the subduction zone.

The next day consisted of a transect across the Schistes Lustres – one of the most complete sections across a fossil accretionary wedge complex consisting of blueschist and eclogite facies metasediments. The fieldwork was punctuated by brief outbursts of some stormy Alpine weather (thankfully one of the only rainy days in the whole trip!).

Day 5 featured a trip to the Lanzo Massif and a shift in focus from the processes operating during Alpine orogenesis to those occurring on the seafloor, prior to subduction. In contrast to many of the Alpine ophiolites seen on this fieldtrip, the Lanzo Massif has largely escaped metamorphic overprinting. Our leader for this day, Othmar Muntener, showed us well-preserved examples of seafloor serpentinisation and discussed the evidence for Lanzo, and some other Alpine ophiolites, belonging to an ultra-slow spreading ridge system. Of particular interest to the group was discussion of evidence for subducted sub-continental lithospheric mantle that would have been exhumed to the seafloor along large-scale detachment faults as part of a slow-spreading ridge system.

For many of us, one of the highlights on the trip was the Monviso area, in the Italian Alps. The two-day trip featured a tour around one of the best exposed fragments of subducted oceanic material, interpreted as a coherent slice of the oceanic crust/mantle interface. Whilst the hiking around the area featured some fantastic vistas of Monviso and the adjacent peaks, it was perhaps equally memorable for the dense clouds that would appear out of nowhere and reduce the visibility to just a few meters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given a group of thirty geologists easily distracted by the rocks, we managed to lose some of the group in the fog! After about a thirty-minute search, and a lot of shouting and whistling, the lost E-FIRE folks were located – already on their way to the Rifugio for an early happy hour.

After the Monviso trip, we took a field break to decompress and to discuss the nascent project ideas the students and postdocs were thinking about in the context of the sites we had visited. It was exciting to hear students bouncing ideas off each other and contemplating how each of their individual projects goals will tie into each other’s. We smell collaboration (and field boots)!

After a well-needed day of rest and relaxation, we drove east to the Ligurian Alps, with the port city of Genoa as our base of operations over the next three days. Here, we drove north, as the serpentinite guru, Marco Scambelluri, led us into the Voltri Massif. In this portion of the Western Alps, it is suggested that convergence between Europe and Apulia occurred at an ocean-ocean plate interface (as opposed to northwest at Monviso, which is suggested to be ocean-continent). We got to contemplate whether changes in plate dynamics here would have resulted in differing metamorphic conditions and preservation of buried lithologies. Our first day was an introduction to the regional geology, and a quick introduction to fieldwork closer to the Mediterranean, with temperatures at times in excess of 100˚F. Much of the terrane is heavily vegetated, so the best field exposures were in riverbeds, like those of the Gorzente River, in the Erro Tobio Unit. The Erro Tobio Unit consists of variably serpentinized ultramafic rocks, with the most striking feature in these rocks being coalescing veins of metamorphic olivine resulting from dehydration during subduction.

The next day, Marco led us to several roadside locations in the Beguia Unit of the Voltri Massif, a region of large (tens to hundreds of meters) lenses of metamorphosed gabbro in a matrix of serpentinite. It has been hypothesized that these lenses may represent a tectonic mélange or simply an extension of what we all observed earlier in the trip. The temperature that day did not let up, and hammering dense Fe-Ti meta-gabbros did not provide a break either (pun intended), but we collected some spectacular samples and witnessed Marco’s expert wielding of a sledge hammer. At the end of days like this, a cool refreshment is always welcome, as well as a nice stroll along the rocky coast of Genoa.

Small Group Fieldwork | 8/8/17 – 8/28/17

Groups of researchers went back to Monviso to collect more stunning examples of slab/mantle fluid-rock interaction, to Dent Blanche for finer-scale sampling of the subduction interface, and out by ferry to explore an extension of the high-pressure Western Alpine rock in Corsica. The authors, with a group of others, went back to the Voltri Massif for more sampling of meta-gabbros and serpentinites, but also to the Apennines, where relics of unsubducted gabbro and serpentinite are preserved. There, we experienced two firsts: tripe (with mixed responses!), and having the carabinieri (the Italian military police) called on us for hammering rocks. This time with smaller groups going back to some of the same locations we visited earlier in the trip, the focus was on more detailed sampling for individual project goals, and expanded discussion of field observations and any tectonic interpretations.

After several days in smaller teams, the E-FIRE group was re-assembled back in Geneva, Switzerland for one more day, and what could possibly beat the adventures we experienced in the field? Why, it’s sample packing! In a parking lot at the Université de Lausanne, we showed each other some of the rocks we collected for our projects, and in some cases, samples we set out to collect for each other’s projects. Samples were packed onto a pallet and wrapped like no rocks had ever been wrapped before. That night, we had one final group dinner in Geneva before we all split up again, where many were back out into field and others were off to the Goldschmidt conference in Paris.

All told, roughly 700 kg of rock was collected by the E-FIRE group during the field excursion, and shipped to Penn State University where the samples will be held in a sample repository. This is of course until we crush, pick at, dissolve, and shoot lasers at them. In all seriousness, it is safe to state that the 2017 ExTerra Field Institute and Research Endeavour was the experience of a lifetime, especially for the early stage researchers; a unique opportunity to interact and initiate collaborations with each other and our new European colleagues, observe and contemplate subduction zone processes in a classic field location, and travel through one of the most beautiful terranes on Earth.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Philippe Agard, Marco Scambelluri, Othmar Müntener, and Samuel Angiboust (along with other European students, postdocs, and research scientists) for their guidance in field logistics and immense knowledge of Western Alps geology. We would like to thank the principal investigators Matt Kohn, Sarah Penniston-Dorland, and Maureen Feineman for the leadership and organizational skills necessary for such a large field-based research endeavor. We finally thank W.O. Bargone for field assistance. This field institute was supported by NSF EAR-1545903 and readers like you. ■

“Report from the Field” was designed to inform the community of real-time, exciting GeoPRISMS -related research. Through this report, the authors expose the excitement, trials, and opportunities to conduct fieldwork, as well as the challenges they may have experienced by deploying research activities in unique geological settings. If you would like to contribute to this series and share your experience on the field, please contact the GeoPRISMS Office at info@geoprisms.nineplanetsllc.com. This opportunity is open to anyone engaged in GeoPRISMS research, from senior researchers to undergraduate students.

We hope to hear from you!