The AACSE Team*

*This report was edited and compiled by Lindsay Worthington.

AACSE PI team: Geoff Abers (Lead PI, Cornell U.), Aubreya Adams (Colgate U.), Peter Haeussler (USGS), Emily Roland (U. of Washington), Susan Schwartz (U. of California Santa Cruz), Anne Sheehan (U. of Colorado), Donna Shillington (Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory), Spahr Webb (Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory), Doug Wiens (Washington U. St. Louis), Lindsay Worthington (U. of New Mexico).

2018 Apply-to-Sail Participants: Collin Brandl (Graduate Student, U. of New Mexico), Enrique Chon (Graduate Student, U. of Colorado), David Heath (Graduate Student, Colorado State U.), Robert Martin-Short (Graduate Student, U. of California Berkeley), Kelly Olsen (Graduate Student, U. of Texas), Holly Rotman (Postdoctoral Researcher, New Mexico Tech), Samantha Hansen (Associate Professor, U. of Alabama), Tiegan Hobbs (Graduate Student, Georgia Tech), Amanda Price (Graduate Student, Washington U. St. Louis), Heather Shaddox (Graduate Student, U. of California Santa Cruz), Jefferson Yarce (Graduate Student, U. of Colorado Boulder), Natalia Ruppert (Seismologist, U. of Alaska Fairbanks)

K-12 Educators On Board: Shannon Hendricks (High School Science Teacher, Anchorage School District), Bethany Essary (High School Science Teacher, Anchorage School District).

The shore-based field teams included graduate student Michael Mann (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory) and undergraduate student Jordan Tockstein (Colgate U.). We thank the captain and crew of the R/V Sikuliaq and the pilots, boat captains and land owners that made these deployments possible. Special thanks to Bill Danforth from the USGS for his bathymetric processing expertise aboard Leg 2 and Patrick Shore from Washington U. for coordinating onshore field logistics and preparing the data for delivery to the DMC.

If you visit Alaska and tell people that you are a seismologist, you are going to hear an earthquake story. The Alaska-Aleutian subduction system is arguably the most seismically active globally, producing more >M8 earthquakes over the last century than any other. As a result, earthquake and tsunami hazard are woven into daily life here. Near downtown Anchorage, you can visit Earthquake Park, occupying part of town that was decimated by a landslide during the 1964 M9.2 event that inspired the term “megathrust” earthquake. If you happen to be in Kodiak on a Wednesday afternoon, you will hear the weekly tsunami siren drill sound throughout the town. Earlier this year that drill was put in to practice as residents made their way through the tsunami evacuation process, meeting up at the school on high ground after midnight on January 29 following the M7.9 earthquake that occurred offshore.

So, how do you study an 800 km section of this subduction zone that is mostly offshore or only accessible via air or boat? Simple. Start with nine Principal Investigators (PIs) and dozens of conference calls; take 85 ocean bottom seismometers (OBS), thirty broadband seismometers, one fishing boat, two float planes, two fixed wing planes, a helicopter, and a 261-ft research ship; add a team of twelve OBS engineers, 24 ships crew, twelve Apply-to-Sail participants, two Alaskan K-12 teachers and two field technicians. Then make the data open and accessible as quickly as possible. This is the Alaska Amphibious Community Seismic Experiment (AACSE) and these are voices from the field.

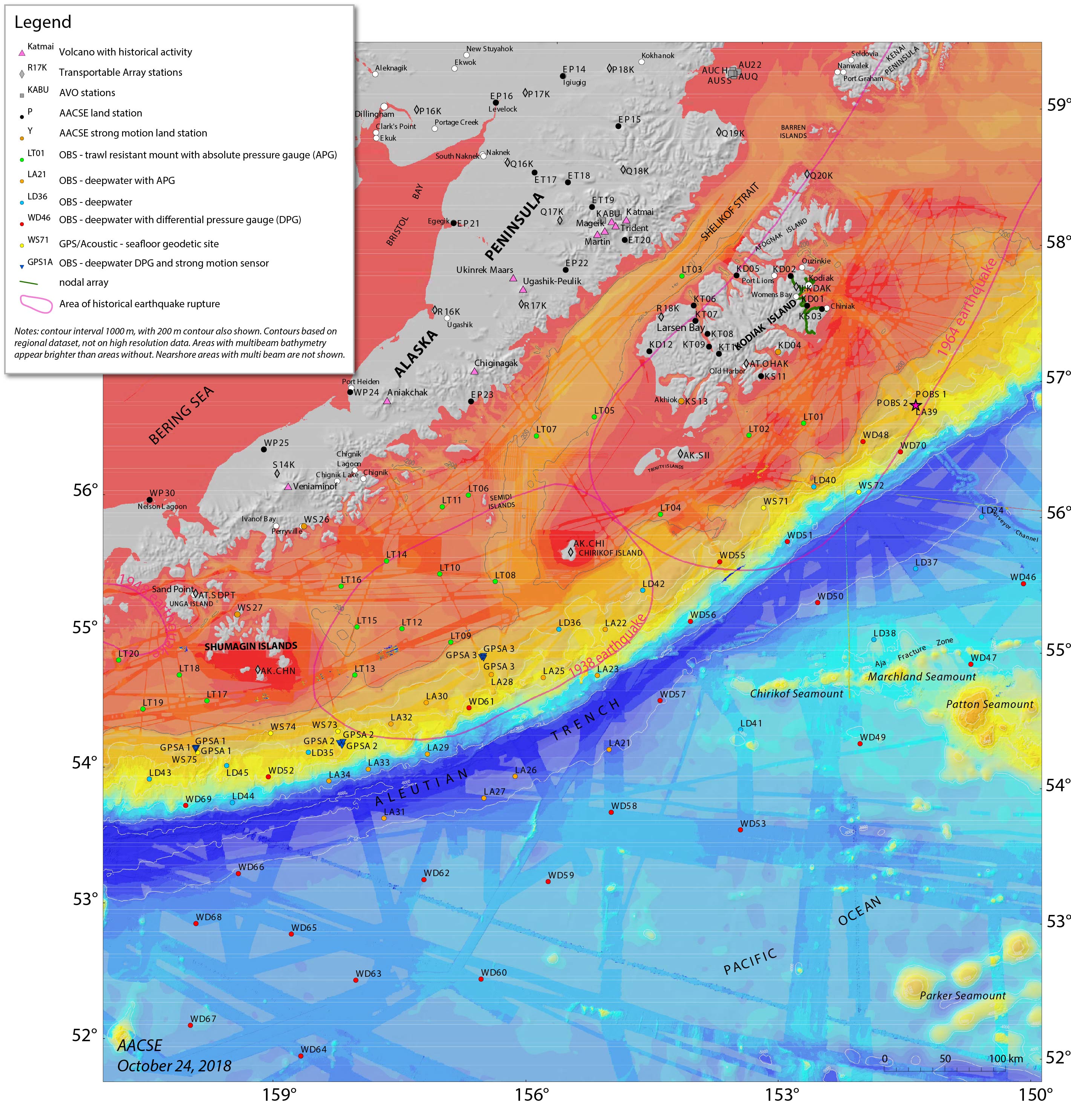

The Alaska Amphibious Community Seismic Experiment (AACSE) deployment map prepared by Peter Haeussle

OBS Deployment Cruise Leg 1 | Seward, AK to Seward, AK – May 9-29, 2018

>> 9 May, 2018 | We are officially underway • It is 8:30am and we are departing Seward dock. We have donned our full-body immersion suits as part of a safety drill, and are now heading towards the first seismometer deployment site, lying in the Shelikof Strait just north of Kodiak Island. We are on one of the most modern and well-equipped scientific research ships in the world. The R/V Sikuliaq was built in 2014 and has a science lab, lounge, dining room, kitchen, gym, and the list goes on. There is even a sauna which apparently can double as a hypothermia recovery room – let’s hope we won’t be using it for that purpose. For cabins, we are treated to the height of oceanographic luxury. The rooms are practical and very comfortable. The Sikuliaq takes its name from the Inupiaq word that means “young sea ice”. Thanks to its round hull, the ship is capable of breaking ice up to 2.5 ft thick, which is essential on polar missions. This also gives it a tendency to move around more in high seas. As we travel, we will be collecting meteorological data such as pressure, temperature, and wind speed. We will also be recording bathymetry data to map the seafloor.

-Robert Martin-Short, University of California Berkeley

>> 10 May, 2018 | Deploying the first OBS instrument • The first OBS (Ocean Bottom Seismometer) is a shallow-water Trawl-Resistant Mounted Seismometer (TRMS), design to resist and deflect the lower leading line of bottom trawl nets. All of the OBSs are instrumented with a seismometer, batteries to last more than fifteen months, transponders to communicate with the ship and burn the wire to release the seismometer for recovery, data logger, temperature sensors, and other equipment necessary to collect these data. The shell for the TRMS itself weighs about 1,300 lbs, the whole instrument weighs about 1,800 lbs. The deployment is a success! After deploying the TRMS, we have to hide from foul weather in Larsen Bay, then assemble more TRMSs. This involves removing the doors and installing brackets to hold equipment, attaching hoods to the pop-up TRMS, checking the transponders to make sure they are properly communicating with the ship, and attaching the transponders. We will stay in the cove and work for a couple hours, then leave once the storm has passed.

-David Heath, Colorado State University

>> 12 May, 2018 | Waiting out the storm • Many of us are taking to personal hobbies and pastimes in between routine status logging. Some people are reading quietly. Others are attempting to catch up on emails, though the internet is particularly slow. Others are taking the opportunity to chat with shipmates, many of whom are still practically strangers after few days on the ship. I am learning that life on a ship provides a unique opportunity for people to connect with each other. I have spent part of the evening receiving a generous guitar lesson from the Chief Steward who is a skilled blues musician. He kindly reached out to play alongside me when he noticed me strumming out on deck. I’ve got to say, my experience thus far has been pretty great, despite the spotty weather and fits of acute nausea.

-Enrique Chon, University of Colorado

OBS Deployment Cruise Leg 2 | Seward, AK to Seward, AK; July 11-24, 2018

>> 11 July, 2018 | Educators Onboard • There are so many people involved in a research cruise like this. There is an entire ship crew, scientists, graduate students, USGS employees, OBS technicians, and, on this trip, there are even two high school science teachers and I am one of those. I am stoked to be on board. My colleague, Shannon Hendricks, and I were selected as part of the Educator Onboard K12 program. Through this program, educators are given the opportunity to participate in research to better understand current science practices. The goal is to use that knowledge to create engaging, authentic lesson plans to share with other educators. It is a little intimidating to meet all of these experts – as science teachers, we know a little bit about a lot of things, and we have a solid enough science foundation to understand what the experts are talking about (most of the time!). This also means we know enough to realize how much we don’t know! It is amazing to get to learn from scientists that have made this their life work. Getting to peek in on their ongoing research makes us better science teachers. And it is nice to know that, just like we tell our own students, there are no stupid questions.

-Bethany Essary, West High School science teacher, Anchorage, AK

>> 23 July, 2018 | The aftershock zone • Day 12 of the cruise, we have just successfully deployed our last OBS, 32 hours ahead of schedule! Half way through this cruise, we decided to move one of the instruments to near the aftershock zone of the M7.9 Offshore Kodiak earthquake. It struck about three hundred kilometers offshore Kodiak Island in the early morning hours of January 23, 2018, in the outer rise region of the Alaska-Aleutian subduction zone. It triggered tsunami warnings and prompted evacuations of thousands of people in Alaskan coastal communities. While the source parameters (such as seismic moment tensor) for the earthquake suggested strike-slip faulting (hence no significant tsunami generated), the true complexity of the source has only become evident through analysis of multiple datasets. At least four conjugate strike-slip faults were involved in the earthquake rupture. However, the distant location of the aftershock source region to the land-based stations made the data analysis and interpretation difficult. On the Leg 1 cruise, a couple of stations were serendipitously placed near or in the aftershock zone. After consultations with the PI group we moved this station to the aftershock cluster. This enhanced network of OBS sensors in the aftershock zone will help characterize the aftershock sequence with much better accuracy.

-Natalia Ruppert, University of Alaska

>> 24 July, 2018 | Good luck • For the past three years, I have been looking at OBS data off the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island, and I always wondered about the logistics behind the dataset of earthquakes. It turns out that deploying ocean bottom seismometers is a huge task that includes multiple people. This experience exceeds all my expectations. I imagined a repetitive process, but every single station has its own challenges: the bathymetry indicates a rough or steep relief so we have to move somewhere close by with a more flat and soft bathymetry; we need to be sure that the temperature sensors are the ideal for specific depths; we fill the sheets with station information and log it in our physical and digital forms, etc. This experience makes me really value all the effort that the science crew did for the deployment and recovery of the data that I am currently working on. For the future seismologists who are going to work with the data, I want to say that we did our best to make sure the seismometers were meticulously deployed and I am sure the recovery crew will be equally careful to collect the year-long log of wiggles from the stations deployed by the first and second legs. Good luck!

-Jefferson Yarce, University of Colorado

Onshore Deployment: Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island and Shumagin Islands; May-June 2018

>> 16 May, 2018 | A for Amphibious • The second A in AACSE stands for Amphibious – fully encompassing the entire subduction zone requires making measurements on land and at sea. The onshore part of the program involves installing instruments on Kodiak Island, the Shumagin Islands (southwest of Kodiak), the Alaska Peninsula and the region around Katmai National Park. These thirty instruments will be placed in remote locations (black circles on the map p.19) accessed by float planes or small fixed-wing planes. One team of three people is installing thirteen sites on Kodiak Island, and a second team is deploying the rest of the sites on the mainland and Shumagin Island. Today the Kodiak team started their first day of work! Like working at sea, the initial work involves unpacking all the gear shipped from across the country, and testing and assembling everything. To make sure everything is working properly, we do a “huddle test,” where we set up all of the seismometers and data loggers in one place and let them collect data for one day. We are fortunate to have been given access to some space in the Kodiak Alaska Fisheries Science Center, a research facility that provides valuable data to the fishing industry and that has a wonderful aquarium. This means we are sometimes sharing the space with sea life, like a large half-decomposed salmon shark! Tomorrow, if all goes well, we can start deploying!

– Geoff Abers, Cornell University

>> 21 May, 2018 | Kodiak Island • The road network on Kodiak Island is confined to the region around the town of Kodiak, so one must travel by boat or plane to reach other parts of this rugged and beautiful island. Eight of the thirteen seismic stations that we are installing here are both off the road system and far from towns with air strips, and we have been traveling to them by float plane. One limitation of using small planes for seismic installations is that there is a weight limit on what you can bring. The float plane we have been using, a de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver, can carry 1,200 lbs. Our field team and equipment for two stations weigh 1,175 lbs! We have to do a weigh-in before our first flight – fortunately they weighed our field team together and not individually. Flying also requires better weather than simply driving to a station. So far, we have found that the weather is worse on the eastern part of Kodiak near Kodiak town but improves to the west. We feel lucky to have had three days in a row where we could fly out to some of our sites. In the last three days, we have installed five stations that have taken us to many corners of Kodiak: McDonald lagoon on the southwestern coast, small Anvil Lake in far western Kodiak and the gorgeous Uyak Bay, a fjord that connects to the ocean in the north and cuts across two thirds of the island. This fjord is enabling us to deploy closely spaced stations over a part of the subduction zone fault where large earthquakes occur, one of the primary targets of this project. Traveling by plane across Kodiak is spectacular; you are treated to stunning views of snow-capped mountains and broad valleys. Sometimes you can see mountain goats lining steep slopes, bears meandering along the shore, and frolicking otters in the water. The views from our seismic sites are really amazing, too, when we look up from orienting sensors and plugging in data loggers. Six down, seven to go for the Kodiak team!

-Donna Shillington, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

>> 30 May, 2018 | Challenging Conditions • The three members of the Sand Point team set sail on the Aleut Mistress to install two strong motion sites on Nagai Island. The day started with beautiful glassy-smooth seas and a calm two hour cruise to our first site on the north side of the island. We loaded our equipment into a skiff, hopped onboard and motored to our chosen landing site. This site was chosen by satellite imagery, and as always, conditions on the ground were a little different than expected. Our landing site was a bit marshy, and we had to lug the equipment uphill through marsh grasses and bushes, and then dig through a foot-thick mat of interwoven vegetation to find a suitably dry site for burial. Anything for good data! The equipment worked like a champ, so our time spent testing it in Sand Point paid off. We left the station after five hours of work – only two-and-a-half times longer than it has taken for any other station thus far! Back on the Aleut Mistress, our captain, Boomer, had boiled some Alaskan crab for our lunch. Hard to get it any fresher!

In the afternoon, the seas started picking up with swells a little over two fathoms (that’s a little over twelve feet for you land-lubbers). While none of our crew suffered from seasickness, there were some flying objects on deck and in the cabin! We hopped back in the skiff when we reached Nagai site #2, and headed toward shore. We got so close, but in the end the boat crew felt it was unsafe to land with the high seas and changing tide. Disappointed, we made the call to cancel the site. It is a hard decision to choose not to install a station. Fortunately, an excellent Plan B fell into our laps. As luck would have it, Boomer owns property near King Cove and offered his place as a home for our new station. So, a fairly tough first day in the field ended on a high note, with the formation of plans for the future. The next three days passed slowly, as our team waited on unanticipated repairs to the plane needed for other installations out of Sand Point. Everybody wants a well-maintained plane, so we waited patiently for the repairs and sorted through and retested equipment in Sand Point. By the time the plane was ready, our team was raring to hit the field again. We hammered out four more stations in just two days, and have nearly finished our work here in Sand Point.

-Aubreya Adams, Colgate University

Reference information