Elizabeth Cottrell (Smithsonian Institution), Katherine A. Kelley (University of Rhode Island), Michelle Coombs (USGS Alaska Volcano Observatory), Elizabeth Grant (University of Washington), Mattia Pistone (Smithsonian Institution), and Katherine Sheppard (UC Santa Barbara)

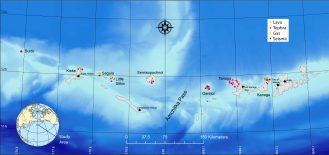

The origin of Earth’s continents is among the most fundamental of questions facing geoscientists today. Though andesitic in composition, continental crust shares many geochemical characteristics with basaltic lavas erupted at subduction zone arc volcanoes, suggesting that subduction zone magmatism somehow manufactures Earth’s continents. Our project goal is to examine one particular attribute shared by arc magmas and continents, unusually low iron contents (sometimes referred to as “calc-alkaline affinity”). Our work will test the roles of magmatic water content, oxygen availability, and parent magma composition on the development of low iron in arc magmas. With this goal in mind, we conducted a three-week field campaign, from September 4-23, to the far Western Aleutian islands of Buldir, Kiska, Segula, Little Sitkin, Semisopochnoi, Gareloi, Tanaga, and Kanaga, home to some of the most calcalkaline lavas on Earth. The goals of the field program were to collect samples of volcanic airfall deposits (tephra), which may preserve glass inclusions within the igneous phenocrysts that will reveal the water contents and oxygenation conditions of these end-member magmas. We conducted our field work from the home base of the R/V Maritime Maid, which anchored in four harbors among these islands, and used a Bell 407 helicopter to access field sites on these eight volcanoes. On the Maid, our GeoPRISMS team of five (Liz Cottrell, Michelle Coombs, Mattia Pistone, Elizabeth Grant, and Katherine Sheppard) was joined by a team of volcanic gas scientists supported by the Deep Carbon Observatory (Tobias Fischer and Taryn Lopez) and a team of geophysicists and field technicians from the Alaska Volcano Observatory (John Lyons, Dane Ketner, and Adrian Bender) who serviced the USGS seismic network on several of these volcanoes for the first time in more than ten years. Project PI Katie Kelley could not be in the field, but participated remotely via satellite phone and internet tools that allowed her to track the ship, helicopter, and us in nearreal time. Our voyage is a great example of how multiple teams can work together to achieve great things.

– Liz Cottrell

Preparing for Danger: Training in Anchorage

2 September 2015 | Anchorage, AK • We’re here. Anchorage, Alaska. Months of planning and training are behind us. In three days we will take a three hour jet flight to the airstrip that is both farthest East and farthest West in the United States (figure out that riddle!). From there, we will board a small boat, The R/V Maritime Maid, and steam West into the uninhabited islands of the Western Aleutians. We will only have what is in our suitcases and what we shipped months ago – and I am scared. I am scared I didn’t prepare my team. I am scared I don’t have the right equipment. I am scared I will make poor decisions. But I am most scared of this pool I’m in. This is the Learn to Return Aviation Land and Water Survival School, more commonly known as “dunker” training, with the unfortunate slogan “Be the One to Come Home!” And I’m thinking “Can’t we all come home?” In this course, we get strapped into metal seats with five-point

harnesses meant to mimic the fuselage of a plane or helicopter. We hover above the water. My instructor, Clint, barks, “Mayday Mayday! This is Echo Alpha Romeo 289 with two souls on board. We are ditching! Ditching! Ditching!” And then WHAM! The seats flip and I impact the water. I can’t see. I can’t breathe. I follow the routine. (0) Don’t panic. (1) Slide my hand. Find the door latch. (2) Open the door. (3) Anchor my hand in the door frame. (4) Slide my other hand to unfasten my belt and pull myself out. Even now, dry, thinking of Clint’s voice sends chills down my spine. One team member doesn’t pass the course. I think of my two kids and wonder if I should just get on a plane home. But somehow, tomorrow I board my flight to Adak. The R/V Maritime Maid and “2-Mike-Hotel” (the Helicopter)

3 September 2015 | Adak, AK • The heli pad on the Maid looks to be about the size of my desk at work. I wonder how it is that my first ever helicopter experience will be taking off from the back of a boat and going over the Bearing Sea to the rim of a volcano. Am I crazy? Our pilot, Dan Leary, is the most experienced pilot at Maritime Helicopters and the absolute best pilot I could ever have hoped for. I soon understand that Captain George Rains, who has sailed these waters for longer than I’ve been alive, isn’t going to take any unnecessary risks.

Weather Orphans the Helicopter

5 September 2015 | Constantine Harbor, Amchitka, AK • The Maritime Maid left port in Adak yesterday destined for harbor in Amchitka. At the time of our departure, the weather was beautiful with sunny, blue skies and a clear view of a steaming white fumarole at the summit of Kiska. The Maid does not sail with the helicopter parked on the deck. Instead, the helicopter normally flies when the boat is underway and they meet up again in harbor. Our plan yesterday was for the helicopter to meet us when we moored in Constantine Harbor, Amchitka but, as we sailed, fog closed in at Adak and kept the helicopter from following us. We have no scientific interest in Amchitka, so we must wait for the helicopter to join us.

8 September 2015 | Kiska Harbor, Kiska, AK • After four days of separation, we are finally reunited with the helicopter! Two days ago, we decided to lift anchor and head to Kiska harbor in the hopes of starting work, with or without the helicopter, and left a fuel cache on Amchitka so the heli could catch up with us as soon as weather permitted. We made the most of our idle time at Amchitka by taking a small skiff to shore, doing a gear shakedown, and taking some “practice” samples. Likewise at Kiska, we were able to skiff to shore yesterday and explore the area around the harbor, view and sample some distal volcanic deposits, and try not to set of any unexploded ordinances leftover from World War II. Kiska was a WWII battleground, occupied by the Japanese for a time before being re-taken by the US, and the historical remnants litter the ground and harbor.

9 September 2015 | Segula Volcano • My first day of real field work! Because of the remoteness of this region, few geological studies have been done here. Today’s target, Segula, hasn’t been visited by geologists since the 1940’s and there are only three known rock analyses from this volcano. We find a gorgeous exposed tephra section in a wide gully and greedily fill our bags with this “black gold.” By the end of the day, I realize with satisfaction that our work will return precious samples from this volcano ripe for new discoveries. – Liz Cottrell

– Elizabeth Grant

Minefield Kiska

9 September, 2015 | Kiska Island • Team tephra is in search of olivine in mafic tephra and we have split up into two sub-teams today so we can cover more ground. Mattia and I are on Kiska, the third westernmost island in the Aleutian chain. The helicopter drops us off on a relatively flat, topographic low near the northern flank of Kiska Volcano, next to a recent lava flow. As the helicopter flies off to assist the other teams, Mattia and I survey the landscape and geologic map to get our bearings. We quickly realize that what we had assumed to be a relatively easy passing is actually a literal and figurative minefield. Instead of consisting of relatively young olivine-rich basalt, the flow is actually composed of older blocks of andesite, twice as wide as we are tall and covered with plants and grasses that reach up to our waists. Not only that, but Kiska is littered with “UXO,” unidentified explosive ordinances, which could be anywhere. From our topographic low, it takes us 45 minutes to scramble the 40 meters to the top of the lava flow, and we arrive at the top sweating and out of breath. As we survey our progress, it dawns on us that we will not be able to cross the rest of this flow; it’s too large and too dangerous. From the comfort of the ship’s galley, we had routed our path across the map’s page, talking about sampling along the way. In reality, the unexpected size of the lava flow provided us with some much-needed perspective about the unforgiving scale of nature and the long-reaching consequences of human activity.

– Katie Kelley

The Virtual Aleutians

10 September 2015 | Narragansett, RI • I wish I were there. And I don’t. Staring at the computer screen, I wonder for the umpteenth time if I made the right decision to stay home. My baby daughter, Miranda, is only four months old, so I couldn’t have gone. Still, I can’t help but have this internal debate daily. It is mid-afternoon here and they will be starting their day in the field soon. I login to a website to check the location of the Maid and the helicopter, both of which pop up on an animated map of our field area. When the helicopter is in flight, it lights up pink and its little propeller turns as it moves across the screen. Watching this is the most exciting part of my shore-based experience.

My phone rings and the caller ID shows “Liz Sat Phone.” Liz says it is raining and I can hear the raindrops over the phone. It seems always to be raining there; she says the volcanoes make their own weather. We quickly debrief on yesterday’s work and go over a plan for the coming day’s activities: our party will deploy one team to Kiska, and the other to Buldir. Buldir is the riskiest flight of the trip, partly because the flight itself is extremely dangerous and partly because they might not find anything useful when they get there, so they are risking life and limb possibly for naught. I am incredibly nervous for them. After we hang up, I login to another website to track Liz’s InReach device, which sends her location every ten minutes. I leave the office just as the helicopter leaves the Maid for Buldir.

Of course, Liz tried to contact me from Buldir while I picked up my children from day care, during the only ten-minute window of my day when I had to pocket my phone. They made it safely there, which is a relief, and I briefly text with Liz’s husband, who is also closely tracking her steps, about how wild it is to watch her walking around. When I get home, we setup my laptop at the dinner table (the only time a computer has ever been allowed at the table, mind you) so my whole family can watch the “action” as it happens. My three year-old daughter has learned the names of all of the volcanoes on the itinerary and asks where Liz and the helicopter are today.

– Mattia Pistone

Kiska Volcano: Ascensus ad coelum et descensus ad Inferos

10 September 2015 • Thirty minutes prior to sunrise. From the vessel bow, while sipping hot tea, I observe that low-elevation clouds still seal the sky. These are not ideal conditions for helicopter flight but this is our last day on Kiska Island and, despite numerous attempts on the flanks, we have yet to find any of the rocks (mafic tephra) that we are looking for. We can only hope to find a fissure in the cloud barrier and find a way to the volcano summit. The wind is with us, however, and it is rapidly clearing up the sky from the dusty clouds. Today, the first team to be deployed by helicopter is the gas team (Tobias Fischer, Taryn Lopez) supported by Adrian Bender, the sedimentologist of “tsunamites” and “stormites,” who is going to be the “radio antenna man” in contact with the Maid while the group collects dangerous volcanic gases on the southwest flank of the volcano summit. The helicopter is fully packed with people, backpacks, and field instruments. There is only one free seat for one person with a backpack. After briefing with the other members of team tephra, it is unanimously decided that I will join the gas team today. I will be tasked with finding and returning rocks from the volcano summit back to the research vessel. I am thrilled! After taking off, our helicopter pilot Dan Leary is like a hawk looking for prey; he finds a spot with broken clouds and steers into it. Thanks to the ascending winds increasing while approaching the hidden east flank of the volcano, we are promptly above the clouds – the sky can also be blue here in the Aleutians. While ascending, the northwest wind is too strong to make any attempt for landing at the volcano summit. Therefore, we are all deployed at about a thousand feet below the volcano summit. It looks like we will have to reach the summit only with some effort and sweat. After a short briefing about work tasks and timetable, and radio communications, the gas team and myself initiate our hike up. Lava flows, loose volcanic bombs and blocks dominate the landscape. After several days at low elevation, I can enjoy this hike without fear of encountering UXO. I am at the top of the crater rim and the landscape in front of me is gorgeous! The volcano crater is in front of me and I feel so small and insignificant. Clusters of loose rocks cover the internal flanks of the volcano. The crater floor is filled with fine volcanic material; it looks like mud. The western side of the volcano has no rim and from there, low-elevation clouds ascend and enter this amphitheater while the northwestern winds blows. I am the lonely spectator of this volcanic show and feel like an explorer – I am the first one to set foot in this volcanic crater… well, after the geologist Robert Coats, who most probably came here during his mapping work in the early 50’s… but, for sure, I am the first Italian here! That’s exciting! Now, back to work. I report the GPS coordinates and field

observations in my book and start to hammer the samples I need. Any sample I take looks beautiful and full of precious information. I wish to take any and all specimens with me since this is the first and last chance we have to collect rocks in the crater of Kiska Volcano during this field mission. But I have to face the reality: I am by myself and cannot carry too many rocks. How time flies! I am quick to collect samples, observations, and data because I have to go back soon. We have now 70 kg of rocks to hike to our helicopter rendez-vous location and I anticipate a very negative reaction from the gas team, who have worked hard for many hours. Instead, I receive generous support, which is typical of an enthusiastic team of people. This is the best reward after a long day of work between volcanic rocks and wind gusts. Together, we march back to the pick-up point. I think this is the greatest day of the field mission here in the Aleutians.

– Katherine Sheppard

On the Edge

10 September 2015 | Kiska Harbor, Kiska, AK • Buldir is a tiny speck of an island about halfway between the much larger masses of Kiska and Attu, all the way out in the far Western reaches of the Aleutian chain. How far out? Let’s just say we didn’t have our passports with us, so we couldn’t except to legally get much further west. There are 45 miles of open water to the east and west of Buldir, which was about a 45-minute flight for our Bell 407 helicopter. This is a perfect amount of time to reminisce about three things: we would be among only a few geologists to visit the volcano in decades, we only had one day to do as much work there as we possibly could, and if anything went wrong while on the island we were all royally screwed. Our day on Buldir had the potential to be the most dangerous day of the trip, mostly due to the long over-water helicopter flight and the remote location. If the helicopter landed but couldn’t take off due to bad weather,

we would be stuck out there until the weather cleared or the boat came to get us. As anyone familiar with the weather in the Aleutians knows, this could take a very, very long time.

As it turned out, we landed, did our work and I soaked in the glory of feeling like a real life explorer. The fog stayed at a respectful distance, the wind stayed manageable, and we were able to take off at the end of the day with minimal excitement. When we landed on the boat 45 minutes later, however, we were ecstatic. We had found amazing tephra samples that suggested an explosive, volatile-rich history for Buldir. Not at all as we were led to expect before the trip, so a resounding success! Only when we had unpacked all the rocks and rid ourselves of our protective gear did our helicopter pilot turn to Liz, let out a breath he seemed to have been holding all day, and say “I am never, ever, ever doing that again.”

– Liz Cottrell

12 September 2015 | Semisopochnoi • With the stressful overwater flight to Buldir behind me, I find myself relaxed and enjoying the flight to Semisopochnoi Volcano. A survey from the air reveals beautiful sections of tephra cut from the vegetated landscape. Michelle and I are able to sample meticulously here all day.

17 September 2015 | Gareloi • I am standing waist-deep in olivine scoria and loving it. Katherine and I fill our sampling bags to bursting and I know we have gotten what we came for. I then hike up to the crater rim – just to take a peek. I am stunned at what I see… a crater lake and active fumaroles! This appears to be a new development since the last time geologists visited this place in 2005 and I am reminded that these are indeed very active volcanoes.

– Michelle Coomb

20 September 2015 | Kanaga • Gas team and two tephra teams got set on Kanaga in the morning, and then boat transited from Hot Springs Bay on Tanaga to the Bay of Islands on the west side of Adak. This was the most spectacular day of the trip so far. Kanaga was completely out and cloud free and I took many beautiful photos. Kanaga is a great island and volcano – deep blue lake in the caldera, spectacular lava flows, deep green grass everywhere. Kanaton Ridge is just screaming out for more and better work, as is the entire island. Visited a few tephra sections as guided by CW’s paper and found some big lapilli pumice falls. No mafic scoria to speak of, unlike Tanaga, and much to our team’s disappointment. I think I found two mafic ashes that may be from Tanaga, which will be interesting to see. We ended the day around 5 pm at the hot springs.■

“Report from the Field” was designed to inform the community of real-time, exciting GeoPRISMS -related research. Through this report, the authors expose the excitement, trials, and opportunities to conduct fieldwork, as well as the challenges they may have experienced by deploying research activities in unique geological settings. If you would like to contribute to this series and share your experience on the field, please contact the GeoPRISMS Office at info@geoprisms.nineplanetsllc.com. This opportunity is open to anyone engaged in GeoPRISMS research, from senior researchers to undergraduate students.

We hope to hear from you!